Advent of Code 2025

This was my first year to commit to do an Advent of Code event in full. In the past, I’ve started feeling a bit fatigued vaguely by day 10, so the fact that this year the event was 12 days definitely helped to pull through until the end.

People often see advent of code as a good chance to experiment with a new language, and I partially agree. This time I’ve decided to go with…Typescript. Definitely not the most esoteric option, but I’ve avoided learning anything about it for long enough.

For context: I’m mostly writing Python these days, have been writing Scala previously for almost 5 years, and have barely touched anything frontend-related.

New things I’ve learned

How to actually set up a TypeScript project

I feel that people in TypeScript ecosystem don’t understand just how convoluted the first step for getting into it is. Yes, this is coming from a Python developer, it’s not much better on this side of the fence. I would argue that this was one of the more complex aspects in the whole endeavor: using the language after the project was properly initialized was pretty easy and intuitive, I’ll save my impressions about it for later.

UnionFind aka Disjoint Set

Day 8 was describing a very special sort of problem:

- There are a set of junction boxes

- Boxes can be connected to each other, forming a circuit.

- Each box can belong to one circuit at the same time

- Joining two different circuits means all entries now belong to a new common circuit

To avoid spoilers, the task was revolving around joining those boxes one-by-one

After writing my crude implementation that worked, but required O(n) of operations for joining circuits, I’ve found out about Disjoint sets, a data structure that provides a couple of nice performance guarantees for such problems. At the heart of this structure are following ideas:

- Each element stores the information about set it belongs to. To do that, each node must have a unique id, and id of a parent.

- Set can be identified by a “root” element id uniquely. Initially we can make so that each node just points to itself as a parent. This means that initially every element is in its own set

- While this sort of looks like a tree, the direction of pointers is reversed from a binary tree, which allows for a root node to have arbitrarily many children.

- To check if two nodes belong to same parent, it’s enough to follow the parent chains of two nodes:

a->b->candd->e->care in same set, whilef->g->his not - Because of (3), during the “find” operation, we can make the tree structure flatter while we “climb the ladder”. This makes future “find” calls on these nodes faster, and does not require updating any nodes other than ones in the reference chain, and makes this structure sort of self-balancing.

- Uniting two sets with this structure is as simple as making root of one node point to the root of the other node:

joining set of node

awith chaina->b->cwithfof chaind->e->frequires settingf.parent = c.idor vice versa

The total implementation of this structure is less than 40 lines of code, about as long as this section of the post. It looks really nice, it is fast, I absolutely love it.

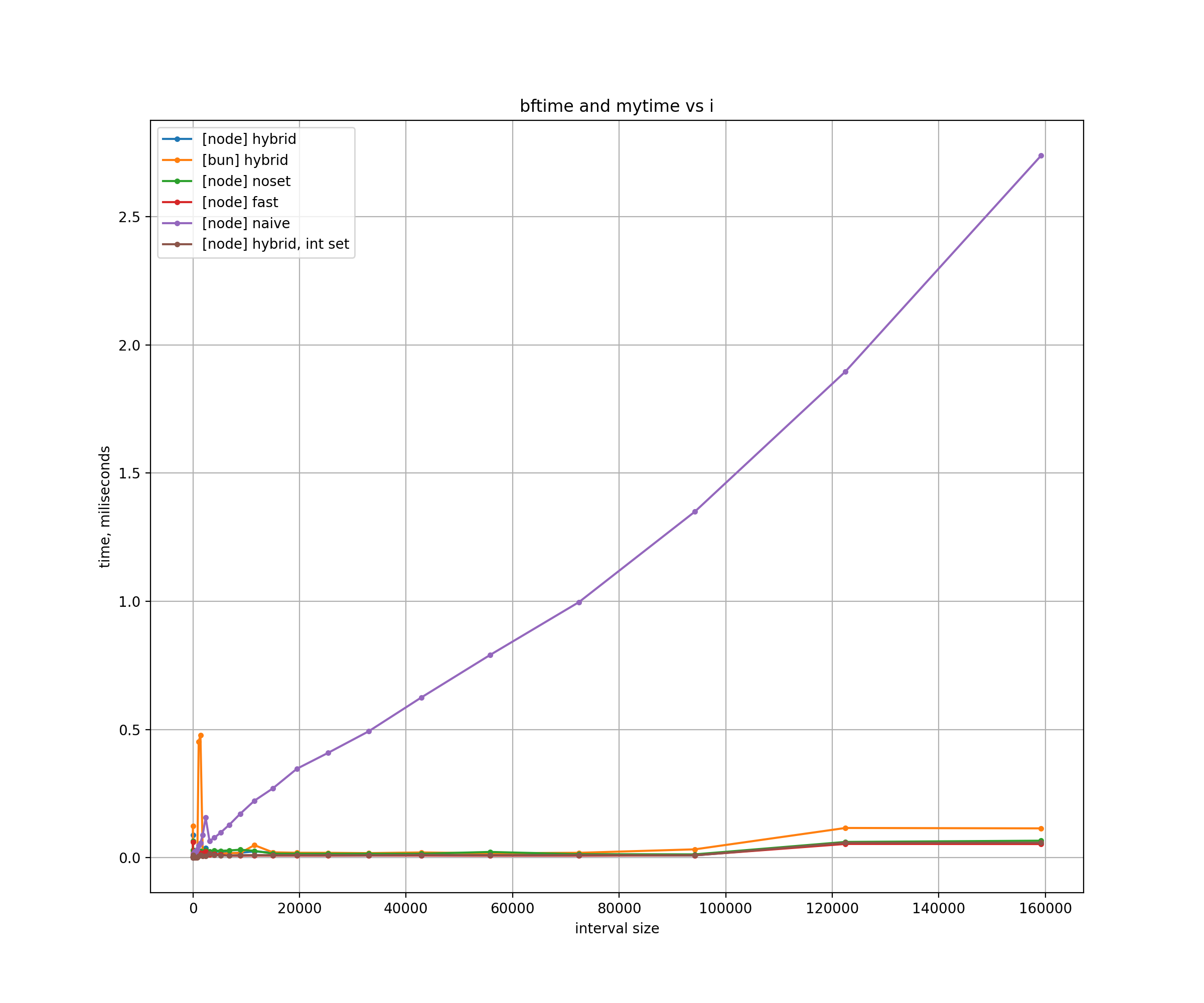

I had a nice opportunity to plot O(n^2) and O(log(n)) algorithms

Fairly early on, at day 2, there was a task in Part 1 that could be solved in two ways:

- Naively iterate for all numbers and all intervals and check if a number is incorrect

- Generate all incorrect numbers within an interval

Intuitively, the first option is horrible:

- Most of numbers in any given interval are not in form of repeated numbers

- You have to cast every number to string to check if first half is repeated

However, for the given input for part 1, the naive approach actually worked and took comparable time to a “good” solution. I then nerd-sniped myself into seeing just how much worse the bad solution is, compared to a good one. Didn’t try to hyper-optimize it, because in principle I wouldn’t use TypeScript if I cared so much about performance, but a difference of 5 minutes vs <1 second feels like a good proof of improvement.

The naive approach actually skyrockets so quickly that I needed to zoom into the graph to show that algorithm not as a vertical line.

I don’t really want to dig too deep into what exactly which line means, but here is the full plot:

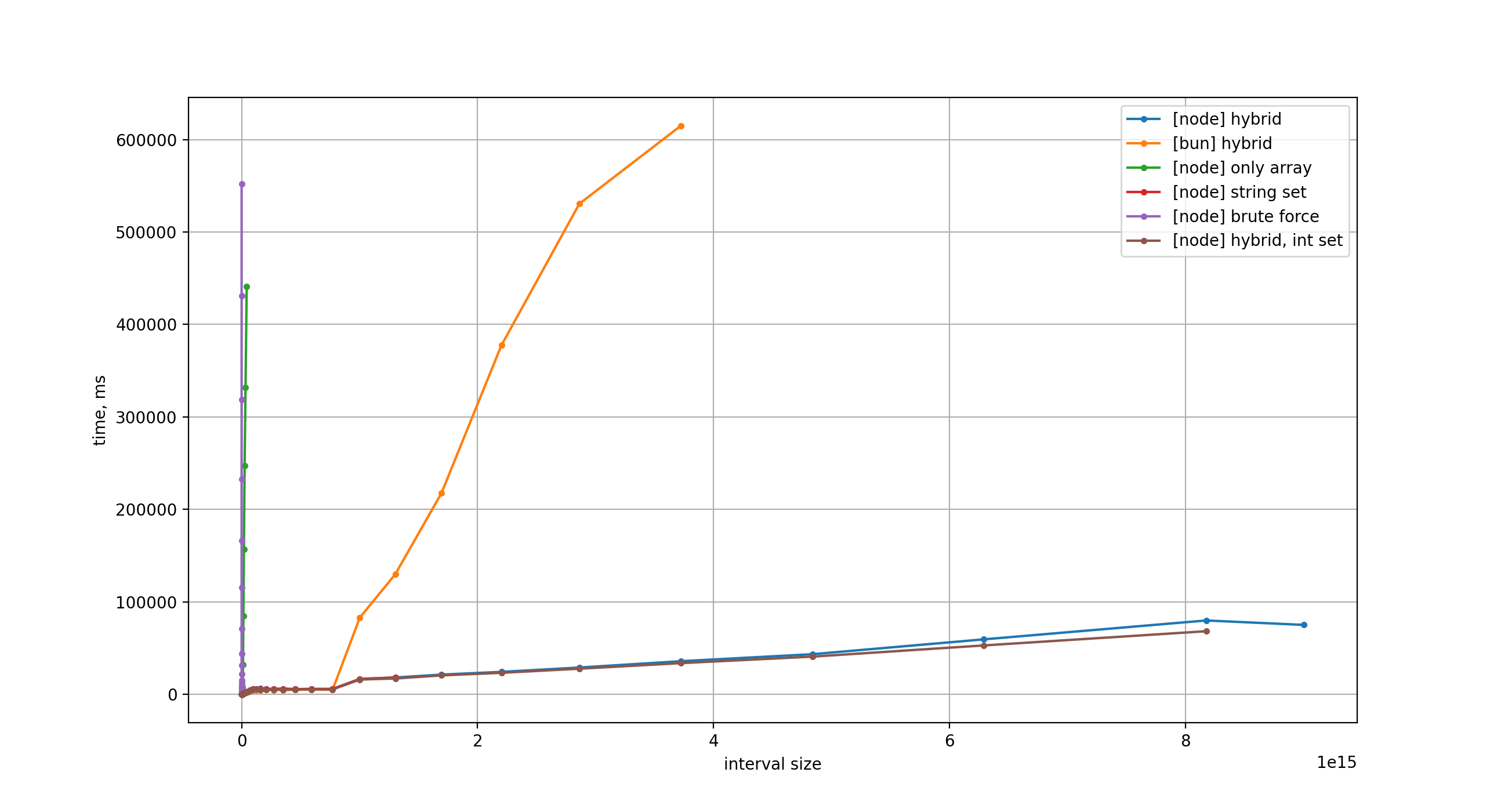

I actually managed calculating intervals for the whole range of safe 52-bit integers in somewhat reasonable amount of time. At least, I didn’t expect prior to running the code that I would actually get there at all within 5 minutes.

On the way, I’ve also discovered that node puts a rather small cap on the size of hashmaps, and in order for me to

actually keep track of all the target numbers in range from 0 to 1e15, I needed to get a bit creative and have this

two-layer cache system, with Hashset serving as fast-insert hash, and a second layer being a sorted array of all

encountered numbers, in which I was able to quickly look up numbers present via binary search (by the way, first time

in a long while since I’ve had to write a binary search by hand, why is it not in standard library exactly?)

And a curious note here is that my solution that works perfectly fine on Node, in Bun got painfully slow real fast, I didn’t have patience to see how long it would take to go through all numbers. Usually Bun got an upper hand over Node, but here specifically, I guess I’ve stumbled into a performance edge-case. If anyone cares to dig deeper into why that happens, the source code is here

Got to learn about theory provers

At day 10, the part 2 was a pretty big jump of difficulty compared to any other task in the event. I’ve had previously played around with SAT solvers for two of my pet projects, so this task sounded familiar, but was sufficiently different to a point where I don’t think using SAT solver is feasible at all. The problem boils down to something like this:

- You have a set of linear equations like

ax1 + bx2 + .... + nxn = y1 - The constants and right hand of equations are given to you, you need to solve for X

- BUT: the caveat is that all unknowns are positive integer values

- There can be multiple ways of satisfying right side of the equation, but only one way has the smallest sum of

xvalues

The search space increases unbelievably quickly - I’m not sure if any sort of brute-force approach would work at all,

maybe if there are some aggressive pruning rules, or a way to prioritize the correct “buttons” - couldn’t figure out those.

Therefore, I started looking for something that feels like a SAT solver, but can work with the problem as above. This is

how I found Z3.

I’m not sure I fully grasp at this point exactly what Z3 is, but it seems like it’s a satisfiability prover, sort of reminds me of Prolog, which I’ve tried for a bit at uni. It is capable of solving a bunch of different math problems, and the one relevant for Advent of Code is called Integer Linear Programming.

After getting that task done I’ve found out that one of the popular algorithms that are able to solve ILP problems is called Simplex method. I didn’t end up implementing it myself, but in principle it sounds pretty interesting.

I still suck at geometry problems

Two tasks this season were about geometry: one required checking for intersections of a line and a rectangle, and another required packing polygons. The intersection problem just got on my nerves a bit, but I pulled through, but the packing tasks I sort of worked around. I half-suspect that the workaround was intended by organizers, since out of 500+ problems given to solve, only for ~20 it was not trivial to check if they could be packed or not. For those that were left I’ve just guessed that there might be a way to do this somehow, and was right. Worst case scenario I guess I would bifurcate and guess number lower.

Maybe this is a sign for me to actually do something related to computational geometry, or computer graphics? Who knows, who knows.

My impressions about TypeScript

In no particular order, some things I’ve thought about when writing solutions:

-

I’ve realized just how much I’ve missed pre/post increment in Python.

i++is much cleaner and easier to type thani+=1, even though it’s incredibly silly to be salty about. -

Some nice convenience functions like

performance.now()that sort of just work. Seems like you don’t have to investigate which specific clock is more suitable for time measuring, and looking up for a monotonic precise clock to measure durations -

Starting from the first days I’ve noticed that using

map/filter/reduceis not just “a bit slower” than the oldforloop, but are a lot slower. This also applies to thefor(let item of coll)as well, obviously. This might be solved by warming up the JIT compiler, but for AOC tasks, which ideally should run once - this has a big impact, for days when tasks could be solved within 300ms, just changing a loop type could shave off 30-40ms of wall time for me. -

let/constenforces you to have some discipline about variable declarations and scoping them. Even though the language is about as dynamic as Python, this small change is surprisingly useful and makes you feel like you’re writing a compiled language. -

IEEE-754 doubles surprisingly were enough for all of the tasks, which I was afraid about. 52 bits of integer mantissa is actually a pretty wide range:

Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGERis actually 16 decimal digits long, and the helper constants allow quickly checking that you’re still operating with integers, if you want to be sure you don’t lose anything.- Python’s decision to automatically promote integer values to proper long integer values with arbitrary precision is

cool in theory, but has a bunch of caveats when working with

numpyarrays, where items have to be sized. But definitely at least option of having this transparently to user is nice.

- Python’s decision to automatically promote integer values to proper long integer values with arbitrary precision is

cool in theory, but has a bunch of caveats when working with

-

The ecosystem for writing TypeScript might be on the same level of Python packaging, might be even worse, since there are more moving parts: while in Python you’re mostly good to go if you have set in stone language version and package versions in a lock file via package manager like

poetry/uv, you can just start writing code wherever if you have something installed. For Typescript, you need:-

Runtime (e.g.

node/bun/deno) -

Package manager (

npm/pnpm/yarn/bun/deno) -

TypeScript compiler (

tsc/bun/deno) -

Wrap the above up with a bow so they play together (adding targets to

npm runand so on)And while the alternative runtimes/ecosystem advertize themselves as “drop-in”, they definitely are not:

-

Multiple solutions that worked in

nodeflat out did not work indeno -

Some packages I’ve tried installing for visualization purposes can be flat out incompatible with your runtime

-

Performance varies wildly between different runtimes. Most of the time

bunis faster than usingtsc-node(at least it saves the compile time), but I’ve had one or two solutions where it was quite the opposite. -

denospecifically is not drop-in replacement at-all because of its’ permission model. I decided to ignore it for this excercise since I was not interested in diving too deep into how to work with it

-

-

It’s much easier to opt into using the type checker properly. Since you have to use a TypeScript compiler to run your code, you will have it typechecked and therefore catch some types of errors quicker. In Python, you have to have a discipline and attach a type checker into your workflow somehow: the easiest one is LSP, but for Advent of Code the usual production solutions (like

pre-commithook) really don’t apply here. -

I miss

scipyandnumpy. Couldn’t find anything similar quickly, but some tasks for Advent of Code are made trivial by having functions to manipulate arrays quickly. At the same time, most of the manipulations I was required to implement in TypeScript were trivial and tedious to do when you do it for the 7th time. At the same time, TypeScript is in completely different domain, where having such tools might not be necessary in day-to-day work. I wonder though, if there is anything even close to those libraries elsewhere. -

Having a debugger in browser is nice: I usually have a browser opened somewhere close, and knowing that I can just press a key to open the console is pretty useful to see all the interactions of some unintuitive standard library at once.

-

undefinedis a sore in the eye. The surprise for me was that unless I was turning TypeScript checks to the absolute strictest, I still got a couple ofundefinederrors. If it was this easy to do in a file less than 300 lines long, then in production it sure might become absolute hell. What surprised me was that even if you type a function to return typeA, there are still multiple ways to sneakily returnundefinedout of it -

Arrays not throwing errors when accessing out of range is…definitely a choice. I suspect that this is one of these things that were part of early JavaScript standard and it’s simply impossible to change at this point. The unfortunate consequence is that the fix on TypeScript side now means that you ave to check every array access to see if it returned

undefinedand enabling a specific rule in compiler -

console.log(obj)pretty-prints object by default. This has its’ limits, but for a bunch of simple cases it was really nice to get out-of-the-box formatting and coloring when I was printing matrices, for example. -

IDE experience is nice. Setting up either VSCode or Neovim for TypeScript is extremely easy - if you’ve already went through the hurdle of setting up the project itself, which, after getting to know the tools is not that complicated. Might be that on other runtimes it is more difficult, but the default path is made really easy. Contrary to Python, where the default path, while might be happy, is something pretty much everyone should avoid, if they want to 1) have external dependencies, and 2) expect to run their code in 2 years with same results. This of course might be wishful thinking on my part, need to try out this code in a year or two and see the results

-

Certain type patterns are made extremely easy to use: limiting string parameter to one of several values does not require an

Enumor a clunkytyping.Literalannotation; specifying plain data structures, dictionary types is all done through onetypeconstruction, and it does not feel overwhelming to use: the types generally look much easier on the eye than in Python. I know this can be abused to no end, but again, the happy path feels nicer to use. -

I was surprised that the “simplest” way to do a deep copy of an object (I’ve had nested array of maps, for example) is to do

JSON.parse(JSON.stringify()), or to implement it manually pretty much, at least that’s what StackOverflow says. Like, seriously? -

The decision on Python side for

map/filter/reduceto return iterators instead of creating collections IMO is much much better than to calculate them eagerly. In TypeScript, when you intuitively write chains of these operations, you end up polluting memory with intermediate garbage, and walk over arrays multiple times unnecessarily. -

I was surprised that in the generator pattern is not popular in TypeScript: there are no features akin to

yield, which makes writing utility generators pretty hard to make. One example of such iterator would be implementing something likeitertools.combinations()in a way where your computer does not explode from keeping all of the combinations of items in memory all at once. I might definitely just not know something here. -

I missed other nice standard library utilities like

functools.lru_cache, aforementioneditertools,heapq,bisect. -

The way you can just call functions without some of the parameters, or with extra parameters gets a huge “huh?” from me. It took me a bit to realize why writing

arr.map(parseInt)suddenly worked differently toarr.map(item => parseInt(item)). And again, by default, no warnings or errors come up. This might be useful in some small amount of cases, but I feel like it’s one step away from giving me a proper currying support in the language, but not going full way.

Conclusion

Will TypeScript be my main language ever? Probably not

Will I use it ever again? Yep, definitely

Is TypeScript completely irredeemable? No, it has a bunch of cool things going for it

Do I regret trying out this language? Absolutely not